Sit-in in Dean Niemi’s Office Continued

c. 1969-1970

Though Jamrich and others questioned whether the decision of the appeals trial had been influenced by the lateness of the hour or by the knowledge of the sit-in, the decision was not overturned. The student judiciary also confirmed that they had no knowledge that the sit-in was going on at the time of the appeals trial. By the day after the sit-in, “…everything was sort of back to normal”, according to McClellan. As the sit-in had occurred the day before Christmas Break, everyone went home thinking that “it was over.”

However, the consequences of the sit-in were not over. According to McClellan, Jamrich had promised not to prosecute the students outside of university discipline. But then…

Jamrich wrote a letter to Ed Quinnell—Ed was…either the full-time or the part-time prosecuting attorney…for Marquette County. He was a good old Marquette guy and very decent man and Jamrich wrote to Ed and said look this is a crime which was committed, trespass and kidnapping—that was the charge…Niemi had claimed that he was held in the office against his will. He got very excited and began to shout and I think he was nervous having so many black people around him all at once. But whatever his reason, he got very upset. So charges were leveled against these black kids in the county, off the campus…and Jamrich was the primary instigator. He filed a complaint against these kids.

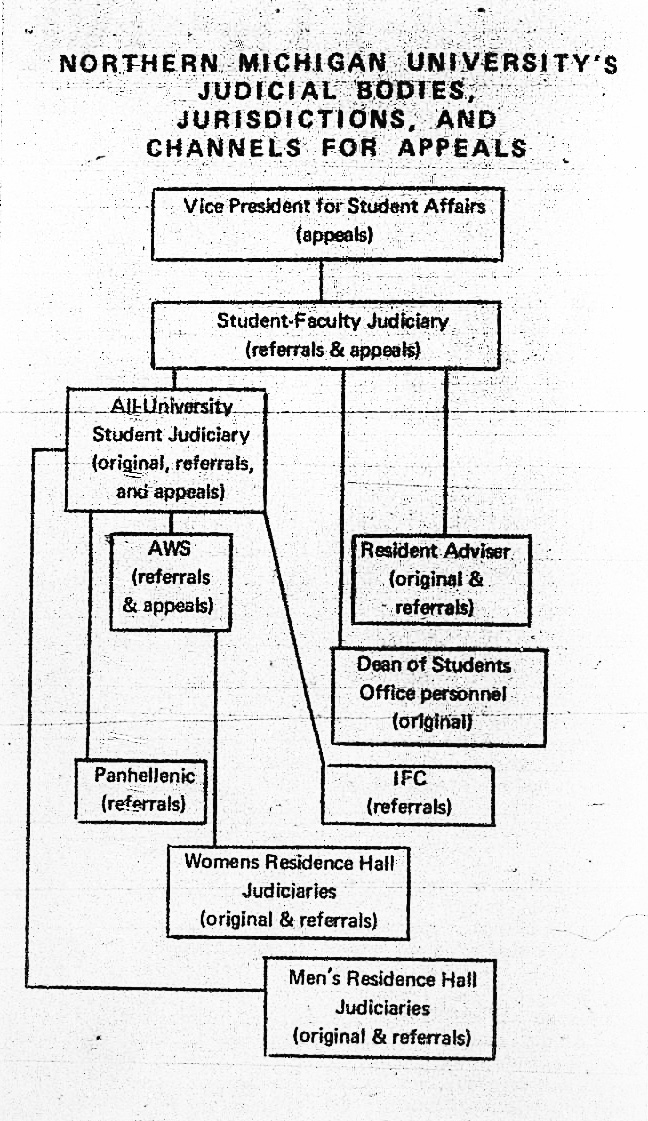

Quinnell began to investigate the sit-in and possible charges of kidnapping (for holding Niemi against his will), assault (threatening Niemi with pieces of wood), and malicious destruction of property. As of early January, however, it was unclear whether or not the county would press charges against the students or even how many students would be disciplined within Northern’s system. A group of ninety-six students signed a paper saying that they were at the sit-in and wished to be charged, but Jamrich decided that only twenty-four students who had been definitively identified would be charged within the university. The Human Rights Commission (HRC), a student and faculty organization at Northern, met with Jamrich on January 8 and asked if he would consider amnesty for all the students involved. Jamrich refused. The HRC then asked for an all African-American jury for the twenty-four students since they felt that Griffis had not been dealt with fairly. Jamrich replied that as Griffis had been found innocent by the court of appeals, there should be no concern about the fairness of the trial. In addition, no African American students had applied for the student judiciary even though the faculty member in charge of the judiciary had sent letters out to specific African American students asking them to apply.

Eventually, the HRC and the administration agreed that when the student judiciary had drawn up charges, they would let David Williams know and have him bring in the students to hear their charges. Jamrich also dropped charges against the BSA as an organization, though he did tell them that the next time they did something he would “adhere to the letter of the law.”

During their meeting, a group of “twelve white students from the nearby Negaunee-Ishpeming area” gathered outside of Jamrich’s office “to show the President [they supported] his actions against the blacks involved in the sit-in.” The students told the Mining Journal that there was “a 50-50 chance that something would be done by white students if the blacks who participated in the sit-in [were] not dealt with firmly.”

The internal university trials of the twenty-four students began in early February after the first semester final exams. All of the students were found innocent—some because they left before damage had occurred and some because they said they had never been told to leave the office and thought that they could remain there until they found out about the verdict of the appeals case. The students again insisted that Dr. Niemi was not held by force. After trying the first nine students, the Student-Faculty Judiciary asked Jamrich if they could forgo trying the rest of the students since the evidence in each case was exactly the same, saying that the trials were only “doing more damage to the University community, causing hard feelings, nothing productive.” Jamrich reluctantly agreed.

The county prosecutor finally filed charges against six people identified as leaders of the protest: Vernon Smalls, Patrick Williams, David Williams, Christopher Poole, Loren Lobban, and Phillip Harper. McClellan, who was heavily involved in the case, “took to calling the case ‘The Case of the Marquette 6,’” presumably after the “Trial of the Chicago Seven” which had concluded a few months before. By mid-April, the name had been picked up by the Northern News when talking about the case.

At first, the students panicked because they had heard that they were going to be arrested and had not been able to find an attorney willing to defend them. Just before their arraignment, however, Robert McClellan was able to help the students find “a crazy guy in town who was a lawyer, sort of a militant radical, Kent Bourland.” Bourland helped with the case full time even though the students were only able to raise a few thousand dollars to pay him.

The trial of the Marquette Six began April 21. A group of about seventy-five white students protested outside of the courthouse to show their support for the Marquette Six and to show that they agreed that there was prejudice and discrimination against African Americans in the Marquette community. They were also protesting the “alleged unfair and unconstitutional treatment given an NMU student who was arrested by Marquette police for displaying an American flag upside-down on the seat of his pants. The group’s leaders said that while in this case the student was white, the treatment he received [was] indicative of the ‘railroading done in the Marquette courts.’”

According to the Northern News, Niemi testified at the trial that,

As he attempted to phone campus security police from the office, Niemi said, “Two black students came up and first asked me not to use the phone, then, as I continued dialing, ordered me not to use the phone.” Niemi said that he tried to leave the office by climbing over the desk but was surrounded by what he termed “a wall of bodies.” Niemi said that he then told Pat Williams, president of the Black Student Association, that he was leaving the office. He testified that Williams told him to “be quiet and sit down if you know what’s good for you.”

…Niemi said that he was threatened during his alleged captivity by two students holding wooden objects. One of the objects, a four-to-five-foot long drapery rod, was wielded by defendant Loren Loban, Niemi said. The other object, a two-by-two inch, thirty-inch long board, was held by an unidentified demonstrator, he said.

Suddenly, a week into the trial, before the defense even had a chance to present their evidence, the case was declared a mistrial and it was never re-opened. According to the Northern News, the judge decided it was a mistrial because of slanted reporting of the sit-in in the Mining Journal, because jury members had been contacted about the case outside of the trial by an unknown person, and because two jurors had already had to be dismissed from the case for discussing it outside of the trial.

McClellan gave an inside look at what happened at the case:

The prosecution presented their case. Jamrich was on the stand quite a lot. There had been a tape made of the student judiciary hearing about Griffis, and that tape had somehow been destroyed. It was a tape which showed the threatened punch and some statements from it. Jamrich never did explain why the tape was destroyed….Witnesses were called about Niemi being frightened for his life, destruction of property in the office, that kind of thing. Anything to build this case, which was very, very flimsy. What we had here was a sit-in. We did not have trespass to any substantial degree, though technically we did, of course, and we certainly did not have kidnapping, that was an absurd charge. I think that was later dropped. Anyway, I recall this very clearly. The prosecution closed on Friday. Saturday morning the case was to be continued and I can remember sitting in the little interview room outside Quinnell’s chambers with the six black guys and Kent Bourland. We were ready to go and put our case on…At that point, the clerk came in from Quinnell’s office and said that the prosecution would like to drop the charges. And we said, we’re not interested. And I was the only witness and I was the only person who was inside…there were other people who were going to witness to the character of these black people, but I was the only person who had been inside and outside who testified the actual condition as an impartial observer, though most people didn’t think I was very impartial, ‘cause they figured I was with the blacks. Anyway, we refused. We refused to back off. We were all set to do our case. Then find out about 11 o’clock the judge declares a mistrial. I don’t know on what grounds exactly; I never did find out. Charges were never then reinstigated. As far as I know, they were either dropped or buried in some judicial way as to ignore because nothing ever came out of this further and this one guy was worried about a felony charge because that’s what it was, kidnapping. He was concerned about the charge because he wanted to go to law school. So the end of the whole matter, the so-called Kaye Hall sit-in, and the trial with the six black guys in Marquette was that all charges were dropped.”

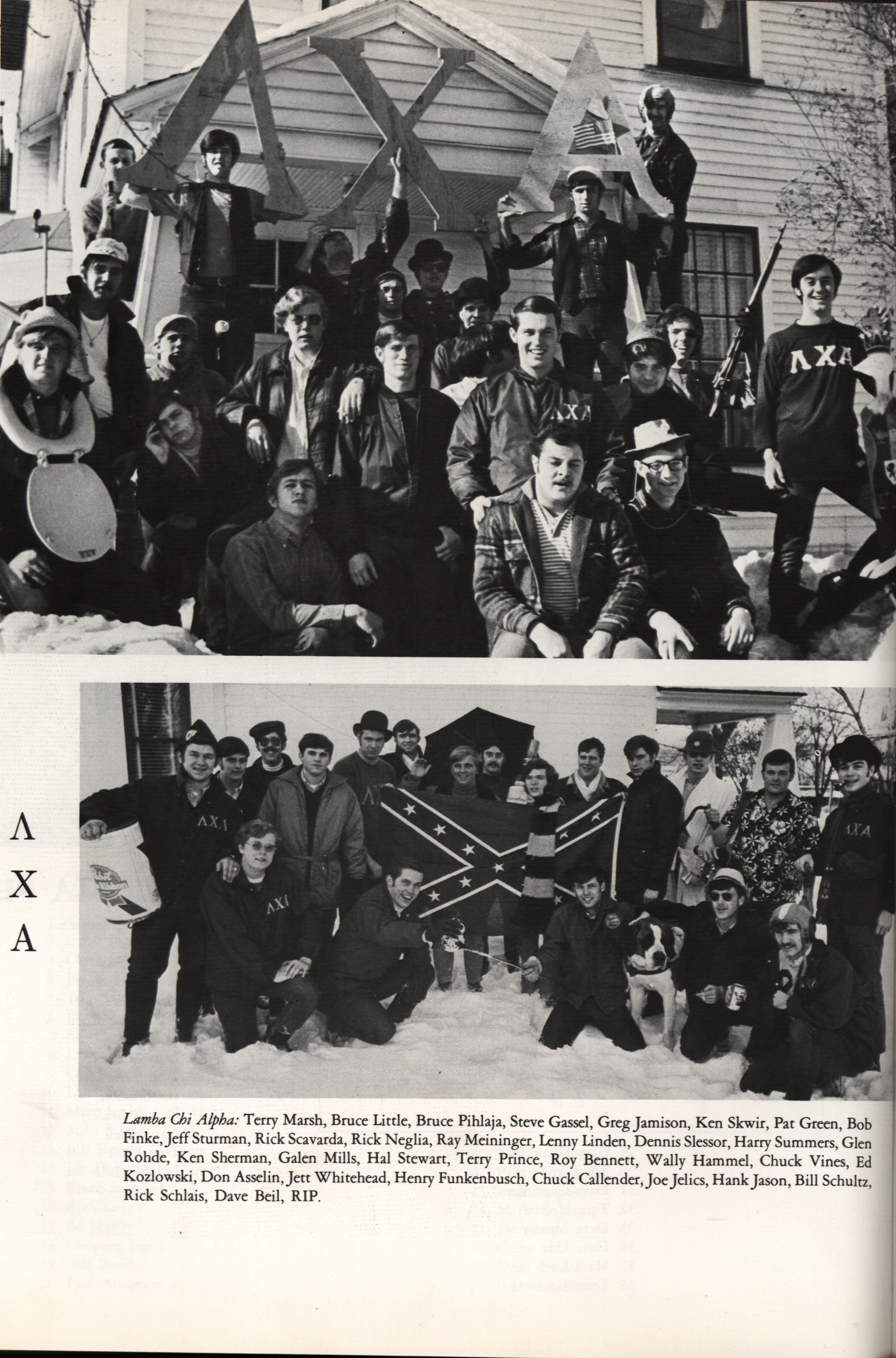

A law came out of the sit-in as well. Dominic Jacobetti, a state representative from the area, proposed a bill “to give the Northern Board of Control authority to adopt ordinances ‘respecting persons and property’ and providing for the enforcement of those rules” in order to “have law and order maintained on the NMU campus” and to show that they would “not tolerate riots, unruly demonstrations, and the destruction of property.” This bill grew to extend questions of whether or not Northern could control student firearms. At the time, students could keep guns unloaded in their dorm rooms. Concerns about the alleged shots taken at black students grew when “[N-word] Hunting Licenses were posted around campus.” Combined with the growing student unrest in recent years, Jacobetti noted that, “If anything ever happened up there…during the deer season in the way of an unruly demonstration, we’d have a regular war on the campus.” Jacobetti said that the bill would teach students “to respect our flag” and that it was necessary to “present a united front in America if we hope to achieve peace on earth and ultimately defeat the threat of Communism to the free world.”

However, in the last weeks of the school year after the trial ended, the tumult did not cease. The events at Kent State, where four students were killed by police at a protest, and in Augusta, Georgia, where six African American students were killed by police after a civil rights march, had ripple effects even in Marquette. After the Kent State shootings, students asked for classes to be cancelled in honor of the four dead, and they were. After the killings in Augusta, Georgia, classes were not cancelled, but the university held a day-long teach-in about the shootings and racial issues in general. African American students also asked Jamrich to cancel classes for the rest of the year because they felt threatened by guns on campus, but Jamrich refused. He did agree to immediately remove all guns from student rooms and lock them in a central room on campus and to ban anyone from carrying a gun on campus.

Of more concern, someone threw an unlit Molotov cocktail bomb into Kaye Hall supposedly because classes were not cancelled for the rest of the year. According to Jamrich,

...the extent of the damages…[included] two windows in Gries Hall, a couple of windows in the Instructional Facility [Old Jamrich Hall], a couple of windows in the Fine Arts Building, in the little theatre of the Olson Library basement—in the little classroom—a Vernor ginger ale bottle thrown through the window had gasoline in it and a cloth, slight burning, but there was no ignition of major source. In the Purchasing Office, we had a broken window and gasoline or high combustible material was found on the floor. A one-quart bottle with some rags and gas in it in the Dean’s Office…a double center window was broken, and a bottle on top of the file cabinet opposite the window. In Dean Reese’s office I’m told there is a double center window, and there was a quart bottle with gasoline and rags in it, and a gin bottle with gasoline and a rag in it in one office which isn’t clearly identified in this report.

A few weeks later, a group of ten African American students went to Lansing and testified that a “state of emergency” existed at Northern and that they felt that no more classes should be held that semester. Again, however, Jamrich, insisted that no state of emergency existed and that he would not cancel classes.

As the school year ended, the Marquette community and Northern began to work towards a better relationship. In the hopes of narrowing the “communications gap,” meetings occurred between students, faculty, administration, and community members to discuss the various tensions between the university and the community. Though many worried that these discussions would never lead to action, they did lead to a community university council.